This is an expanded version of the article “The Search for a Quality Physician: The Rise of Alternative Healthcare Delivery Models” previously posted on this website.

Have you found yourself in need of a new physician? You relocated. Your physician retired. You need a specialist. Your current practitioner (or their office staff) no longer meets your needs. Whatever the reason, the search for a new practitioner is not as simple as it once was. In years past, you surveyed family and friends, sought advice from other practitioners, and very importantly, checked with your insurance company. Today however, thanks to the pervasive reach of the internet, there are a myriad of additional resources at one’s disposal: Yelp, Healthgrades, Vitals, Zocdoc, Ratemds and U.S. News and World Reports – Health, to name a few. As a result, you may think the search for respected and qualified practitioners has become easier. Sadly, you would be mistaken.

Increasing Appointment Wait Times

Whether you need to schedule a sick visit, specialist visit, or annual physical exam, a potentially lengthy waiting period for an appointment is very likely in your future. A poll of family, friends, colleagues, a look at investigative journalism articles, and a review of research-based studies (health surveys and health economics), will all reveal longer than expected – or desired – wait times. Why these delays? The answer is likely related to a complex set of factors: (1) increased patient demand, (2) an aging American population requiring more specialized care, (3) physician supply and demand, (4) increased medical specialization, (5) stagnant growth in the surgical specialties, (6) an aging physician population, (7) the need to expand graduate medical education and residency training slots, and (8) a convoluted insurance physician reimbursement process, including a continued drive to shift away from a fee-for-service payer-provider reimbursement model to a long-overdue, quality-focused, value-based reimbursement model. Underlying these issues are political and economic dynamics that influence healthcare service providers’ ability to meet demand, such as the unprecedented increase in undocumented and illegal immigration over the last couple of years which, should it continue at current rates, will undoubtedly further stress the American healthcare system.

Impact of COVID

It would be negligent not to mention the devastating impact the COVID-19 pandemic had on the healthcare industry. A study conducted by Stanford University and the University of Southern California examined the number of excess physician deaths between March 2020 and December 2021. They reported “4,511 deaths representing 622 more deaths than expected among physicians.”1 It is a little more difficult to get an accurate representation of the number of nurses who died from COVID-19. Much of the published literature focuses on deaths among nursing home residents and staff, who were hit particularly hard. The publication The Guardian, in partnership with Kaiser Health News, attempted to document every healthcare worker (doctor, nurse, aide, paramedic, custodian, etc.) who lost their life to COVID while on the job between March 2020 and April 2021, the first year of the pandemic.2 They reported more than 3,600 healthcare deaths, with approximately “one in three” being nurses. Needless to say, we know that number only increased in subsequent years.

COVID brought with it unprecedented crises for hospitals and healthcare providers – insufficient numbers of beds, ventilators, medication, supplies, and personnel, to name a few. Those on the front lines experienced physical, emotional and mental exhaustion leading to high levels of stress, anxiety and depression. Burnout and exhaustion ensued, which led to early retirement for many physicians and nurses, thereby further worsening the existing shortage of physicians and nurses.

Association of American Medical Colleges Physician Shortage Projections

In order to better understand the rise in alternative healthcare delivery models, we will examine some of the complex dynamics between the aforementioned factors impacting the current, and projected, physician shortage. These issues influence not only the demand and supply of healthcare providers, but also patient satisfaction and retention. COVID-19 aside, the American Association of Medical Colleges’ (AAMC) publication “The Complexities of Physician Supply and Demand: Projections From 2019 to 2034” has projected a shortage of physicians ranging from 37,800 to 124,000 by 2034. The projected shortage includes roughly 17,800 to 48,000 primary care physicians and between 21,000 and 77,1000 specialists.3 Increased population growth, primarily amongst those 65 years of age and older, along with an aging physician workforce have a bearing on these projections.3 Potential identified solutions include expanded use of physician extenders (advanced practice nurses -APRNs and physician assistants – PAs), changes to the graduate medical education pipeline, and identification of factors that may be hampering the growth of surgical specialties.3

2023 Trends Shaping the Health Economy

Given that the issues noted by the AAMC have been known for quite some time, you may wonder, why do hospital and medical administrators repeatedly find themselves precariously unprepared for changes in the American health economy? Sanjulan Jain PHD, a respected health economist and Senior Vice President at Trilliant Health, states:

“. . . As an industry, we are satisfied with data that is “directionally correct” instead of demanding data that is “statistically representative” and market specific. Moreover, the industry habitually extrapolates a discrete data point, something that is true of 5% or 10% of the population, to 100% of the population. We say healthcare is local and yet rely on national trends that fail to account for geographical nuances, even though what is true of one market is rarely reflective of another.”4

Jain’s 2023 Trends Shaping the Health Economy combines original research from diverse healthcare datasets with novel machine learning models to deftly render a picture of healthcare trends we can expect in the coming years. These trends are expected to impact all players that have a stake in the healthcare game – from insurance providers to hospitals to physicians and ultimately to consumers. Jain has identified the following ten trends: (1) an eroding commercial market, (2) the unraveling of health of American consumers, (3) investments in prescription drugs and diagnostics, (4) a non-enthusiastic demand for healthcare services, (5) consumer behaviors that reveal patient decision making practices, (6) elimination of traditional healthcare intermediaries, (7) constrained supply of providers, (8) overstated monopolistic effects, (9) employers paying more for less healthcare services, and (10) lower than expected market rate returns.4

Table 1 (See Annex I) highlights aspects of the aforementioned ten trends identified by Jain (2023), that either indirectly or directly influence overall patient satisfaction, or dissatisfaction, with healthcare services. Community hospitals are being purchased by healthcare systems.4 Hospitals are losing money to ambulatory care centers.4 Primary care physicians are losing money to pharmacy associated care clinics (i.e., CVS MinuteClinics, Oak Street Health).4 Independent physician practices are being consolidated or vertically integrated into larger specialty groups, hospital systems or health maintenance organizations (HMOs).4 Retiring physicians are outpacing newer physicians.4 Non-patient-centric business (biopharmaceutical, consulting firms, insurers, etc.) are competing with hospitals and physician group practices for providers. As a result, the supply of physicians and surgeons may not meet the demand, especially in impacted geographical regions.4

So, why do Jain’s 10 Trends Shaping the Health Economy matter? Because as Jain points out, “The winners in healthcare’s negative-sum game will be those who deliver value for money.”4 This slow-motion pivot towards value, and behind-the-scenes struggles over which interests get to define what “value” means, signal big changes underway in our healthcare system. While this is important for providers and payers, it is also important to the average consumer who is increasingly finding themselves in the position of having to seek out the most optimal combination of quality and price for a given healthcare service. This is especially important for the uninsured and those with high deductible healthcare plans.

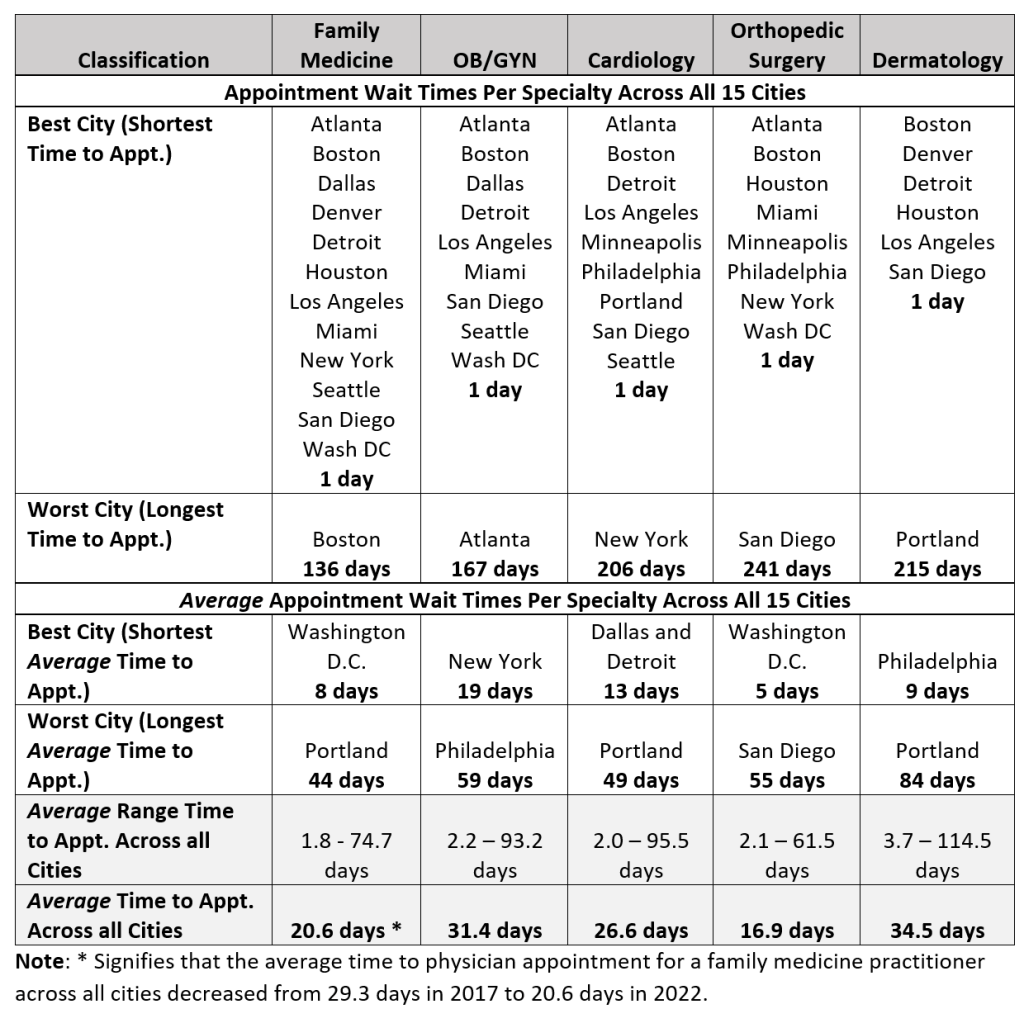

2022 Survey of Physician Wait Times

A frequently cited study, AMN/Merritt Hawkins’ 2022 Survey of Physicians Appointment Wait Times and Medicare and Medicaid Acceptance Rates is conducted every few years (2004, 2009, 2014, and 2017) to assess new patient access to physicians for non-urgent conditions.5 Each surveyed year focuses on five specialties (family medicine, obstetrics and gynecology, cardiology, orthopedic surgery and dermatology) in fifteen United States (US) metropolitan areas (Atlanta, Boston, Dallas, Denver, Detroit, Houston, Los Angeles, Miami, Minneapolis, New York, Philadelphia, Portland, San Diego, Seattle, and Washington D.C.).5 Researchers randomly select physicians from online listings (“Yellow Pages, or Healthgrades or through search engines such as Google”) and attempt to schedule “the first available time for a new patient appointment.” 5 If asked, a hypothetical, non-urgent reason is provided as motivation for the appointment.5

Survey results from AMN/Merritt Hawkins’ 2022 study continue the year over year trend of increasing average wait times from time scheduled to first available new patient appointment across all fifteen US cities surveyed.5 2022 data showed an 8% increase (26.0 days) over 2017 data (24.1 days), which increased 30% from 2014.5-6 The average wait time for all specialists increased from 2017 to 2022, with the exception of family practice, which saw a 30% decrease (29.3 days to 20.6 days).5

Table 2 provides a summary of AMN/Merritt Hawkins’ 2022 average findings. There was a wide average range from initiation to time of appointment across all specialties (1.8 to 114.5 days).

Table 2: Summary Statistics for AMN/Merritt Hawkins’ 2022 Survey of Physicians Appointment Wait Times and Medicare and Medicaid Acceptance Rates 5

While the aforementioned AMN/Merritt Hawkins’ study may serve as a baseline assessment, the sample size for each specialty in each large US metropolitan area is fairly small; typically less than 20 offices contacted.5 In addition, the average wait times for new patients at randomly selected offices are likely markedly different from the average wait times for both new patients and existing patients for highly rated, in-demand physicians and surgeons. Unfortunately, there is very little research into this latter group. Like AMN/Merritt Hawkins’ survey research, the vast amount of research into physician wait times centers around new patient appointments, with no discernable difference made for physician quality, experience or ratings.

Given the lack of research dedicated to both existing patients’ wait times, and new patient wait times, for highly regarded physicians and surgeons, a cynical person may conclude that administrative healthcare personnel no longer value physician quality. As long as one is able to consult any physician with valid credentials – no matter if that physician is a shoddy medical professional with numerous malpractice suits, all is still well in the healthcare universe.

Actual Patient Experiences – Both Existing and New Patient

Poll of Family and Friends

The dearth of appropriately designed scientific research has led me to conduct a cursory poll of family and friends. The results: scheduling a sick visit can take up to 2 weeks. A specialist visit has a conservative 1-3 month delay, while an annual exam takes careful planning and forethought to secure an appointment roughly 3-6 months in the future. Sadly, reported wait times have increased in the last year alone. These approximate times are more in line with the “longest time to appointment” times recorded in the AMN/Merritt Hawkins’ survey, not their often-reported average wait times.5 Heaven forbid your practitioner falls ill, goes on vacation, or simply elects to take some personal time. Where is one to turn? You may try to make an appointment with the on-call or “covering” doctor. Your success will likely depend on your ability to actually speak with the covering practitioner’s office staff, or your willingness to wait 2-4 hours for a same-day walk-in appointment (if even permitted).

Los Angeles Times’ Investigative Reporting

An unexpected source of information on long wait times comes from local-market investigative news articles, such as the one conducted by the Los Angeles Times investigative team (2020).7 Following an anonymous tip from a physician working for the Los Angeles County Department of Health Services, the Times conducted a nearly two-year investigation into extended physician wait times.7 The Times noted that several patients died waiting to be seen by specialists, some after having waited eight months or longer for referral appointments that never happened.7 “Cardiology, oncology, gastroenterology and nephrology,” were identified as critical specialties with long wait times.7 Upon closer examination, the Times found the average patient wait time was 89 days, with a median of 66 days.7 The Times’ findings were disputed by various county officials.7 However, a Department of Health Services spokeswoman made the following jarringly memorable statement, “the Department of Health Services considers ‘next available’ appointments timely as long as they occur within six months [emphasis added].”7

Zocdoc (Online Appointment Scheduler) Survey

In an attempt to better understand and improve reported physician wait times, such as those described above, Oliver Kharraz MD, the CEO of Zocdoc, an online physician appointment scheduler, sought to gain insight into the disturbing trend.8 A survey conducted by Zocdoc (2019) revealed that “Nearly 3 in 4 Americans say it’s easier to go to the ER than to get a doctor’s appointment.”8 Therefore, it is not surprising that “even though 84% of Americans have an established relationship with a primary care physician, 65% would still visit the ER if they couldn’t get in to see a doctor at the office quickly enough.”8 Based upon these findings, one may surmise that Emergency Room (ER) visits would likely be on the rise. However, that assumption would be incorrect. According to the Centers for Disease Control (CDC), ER visits have been fairly stable from 2016-2021, with a slight spike in 2019.9 Wait times, however, vary depending upon location, regionally as well as locally.10

Share of Care and Share of Wallet Measurements

The above-mentioned factors, and those outlined in more detail in Tables 1 and 2, provide insight into why the average person is finding it increasingly more difficult to schedule an appointment with their existing practitioner, let alone establish a relationship with a new practitioner or specialist. What the original data failed to address, however, is the growing dissent that physicians and patients alike have with the current and projected healthcare marketplace. So, what is being done to improve overall satisfaction as evidenced by patient recruitment and retention? DJ Sullivan and Travis Ansel at HSG Advisors, a healthcare consulting firm specializing in physician networking and integration, published “Patient Share of Care: Share of Wallet for Healthcare”11 (2021). “Share of Care,” refers to the total amount a person spends on their healthcare (inpatient, outpatient, ambulatory care services, physician offices, etc.). This measure is then used to gauge patient loyalty in various patient populations.11 Sullivan and Ansel note that “if a health system is not successful in retaining these patients [primary care patients], it will likely not be successful overall.”11 The goal for a healthcare system is to retain patients, and to minimize loss to the competition, especially those in the same service area. This measurement represents the healthcare system’s “Share of Wallet.”11

According to Sullivan and Ansel, “Share of Wallet” measures have been underutilized in the health services industry.11 They recommend identifying and tracking the spending patterns of select patient populations at three different levels: (1) overall market level (health systems broad service area), (2) access point (physician office, hospital inpatient, etc.) and (3) service line and sub-service line levels: Service line (for example: Cardiovascular, orthopedics, etc.) and subline (for example: general medical cardiology, cardiac electrophysiology or sports medicine, joint replacement).11 They suggest that at a minimum, the following three patient populations should have their own “Share of Care” measurement: primary care patients, emergency department patients and urgent/immediate care patients.11 By capturing this information, executive leadership and administration can identify recruitment and retention strategies to benefit their most important patient populations. Such measures may include recruitment not only of primary care providers, but also select specialty physicians and surgeons that meet the demands of the key patient populations.11 The overarching goal is long-term stability of the health system. “Patient Share of Care should be a health system’s primary metric to measure patient loyalty and inform strategic plan development.”11

Politicalization of Healthcare

Recent Changes

The Affordable Care Act (ACA), enacted in March 2010, aimed to make healthcare affordable (via low-income subsidies and expanded Medicaid programs), increase access, provide protections and rights to patients (no pre-existing condition denials or higher fees, no annual or life-time limits), no-cost preventative care, and enhanced protections for women and children.12 In addition to added benefits, protections and rights for American citizens, California (2024) has also extended full Medi-Cal (California’s Medicaid) benefits to over 700,000 undocumented and illegal immigrants between the ages of 26-49 years.13 This policy expands upon a 2022 law that imparted full Medi-Cal benefits to undocumented and illegal immigrants aged 50 and older, and a 2020 law that gave children and young adults under the age of 26 full healthcare benefits regardless of their immigration status.14-15

California’s Governor Newsom declared the extension “a transformative step towards strengthening the health care system for all Californians.”13 However, given the above-mentioned Los Angeles Times’ investigative reporting on the exceptionally long, and at times fatal, patient wait times in California, along with record numbers of homeless16 (most without access to healthcare),17 an ever increasing opioid epidemic,18 and considering that “40 percent of the state’s population are [already] enrolled in Medi-Cal,”19 some argue that Newsom is failing its legal citizens by putting an additional strain on an already buckling Medi-Cal system and state budget in favor of partisan political theatrics.20-21

While there are many positives associated with a larger number of consumers (both legal and illegal) being insured, there are also a few negatives. One of the most prominent being an exacerbation of the physician shortage, as more consumers seek access to health professionals. The inevitable result, a growing frustration with barriers to access and ever-increasing wait times (themselves a barrier to access).

Transforming Healthcare “Back to the Future”

Physicians

While the more scientific approach of analyzing, interpreting and projecting future trends in healthcare service done by Trilliant Healthcare’s Jain and HSG’s Sullivan and Ansel is indeed informative, do they provide enough insight to satisfy consumers and physicians? Considering the vast majority of healthcare consumers will never see, read or be told about these studies, the answer for them is likely “no.” As for physicians, they no longer have the upper hand in the payer-provider reimbursement game. Understandably, payers are demanding higher quality at a lower cost. However, there is no fixed definition for what “quality” means. Additionally, a growing number of health care systems are becoming more reliant on non-physician care providers (nurse practitioners and physician assistants) and vertical integration of health services, which often results in impersonal, standardized care plans and an inability to establish personal patient-physician relationships.

Therefore, it is unsurprising that the collective body of American physicians lack a cohesive solution. Not all physicians are willing to continue with the status quo (many overworked, burnt-out and stressed) until the healthcare system they are a member of finally figures out its next steps. It is true that some physicians, especially young primary care physicians, may feel they have no choice but to continue with the current state of affairs, as they lack the experience and patient panel size (patient load) to abandon the current model. However, more experienced physicians who have become dismayed by the pressure to maintain large patient panels, which significantly limit time-per-patient, while grappling with payer reimbursement and other administrative tasks, may be seeking alternatives. These senior physicians are more likely to have loyal patient populations whose healthcare they have been managing for decades. As a result, they may be more inclined to entertain the switch to a membership-based alternative healthcare model. In so doing, these physicians are able to reduce their overall patient panel, increase the amount of time spent with patients, and in the case of direct primary care (DPC), significantly reduce insurer-related paperwork (actual paper or electronic medical records) and personnel. All, without sacrificing revenues. The result: their patient-physician relationships purportedly become more personal, comprehensive, and less stressful.

Patients

The average person does not care about regulatory changes (such as Diagnosis Related Groups (DRGs) and the Tax Equity and Fiscal Responsibility Act (1982)), or the ever-restructuring healthcare marketplace with its mergers and acquisitions, and inevitable monopolies among providers and payers. They don’t care about the overhead an electronic medical record system brings. Nor do they understand the interplay between the number of medical schools, subsidized residency spots and the shortage of providers in many marketplaces. What they do care about is having to wait 3 to 6 plus months for an appointment, only to be rushed through their visit, leaving with more questions than when they arrived. They want a practitioner who, at the very least, gives the impression that they understand both their individual selves and the trajectory of the medical condition they are presenting with.

Enter Concierge and DPC Medicine

Concierge Medicine

What is concierge medicine? This refers to membership-based (fee-based) medical practices. Concierge medicine, as we recognize it today, had its inception in Seattle, Washington in 1996 when Drs. Maron and Hall tailored their practice to wealthy consumers able to pay the $13,200 – $20,000 yearly family membership fee.22 As interest in concierge medicine grew and services expanded, the price of entry decreased substantially. Currently, members pay their practitioner, or medical practice, a fee which ranges on average from $1500-$5000/per person per year. Practitioners that hold two or more board certifications tend to demand higher membership rates.23 Also, one can expect higher fees in more affluent areas. The fee, generally billed monthly, biannually, or yearly, serves as a retainer; reminiscent of businesses and wealthy individuals who have attorneys on retainer, and therefore do not pay hourly fees for services. This fee affords concierge practitioners the ability to reduce their patient panel size (patient load), so that members can receive 24/7 practitioner access, 365 days/year, including weekends, emergency treatment and house calls.24 Additionally, membership typically includes a set of pre-defined services that are included with the membership, and are separate from services that would be billed to a member’s healthcare insurance provider.

Concierge practitioners purport to be able to provide on-demand, unrushed and comprehensive care, allowing for detailed discussions, assessments and evaluations without delay.25 As an added benefit, many concierge practices offer multi-specialty services with expedited referrals. Larger concierge practices frequently offer functional and integrative medicine, and holistic care (IV vitamins, allergy testing, acupuncture, chiropractic treatment, ayurvedic medicine, naturopathic nutrition, etc.), advanced diagnostic radiology services and board-certified emergency room physicians.24,26 Some even accompany their patients to specialist visits.27 The goal of concierge practitioners is to optimize each member’s health by prioritizing patient care and enhancing the relationship between practitioner and patient. Ideally, the patient-physician relationship is to advance from patient and caregiver to partners in healthcare. Individuals desiring immediate practitioner access, and those with chronic conditions requiring ongoing evaluation and care, reportedly most appreciate concierge medicine.

It is important to note that concierge practices are not limited to primary care (including family practice and internal medicine practitioners), or individual or small group practices. According to Concierge Medicine Today, the top six specialties that have incorporated a concierge medicine model include: family medicine, internal medicine, osteopathic physician, cardiology, nephrology and pediatric medicine.28 Additionally, some university-affiliated healthcare systems also have separate concierge medicine groups; the University of Pennsylvania, University of Miami and Duke University to name a few. The University of Pennsylvania offers Penn Medicine. According to their website, this program “emphasizes a strong patient-physician relationship, a focus on preventive care and long-term wellness, and unparalleled service.”29 The University of Miami offers UHealth Premier membership, while Duke Health offers Duke Signature Care.30-31 Each stress personalized care, greater access to one’s primary care physician, same or next day visit, assistance with referrals, longer visits and continuity of care.29-31 While all patients, including those with traditional healthcare plans would welcome similar benefits, these prominent University healthcare systems recognize the limited ability of most primary care providers, including their own, to provide them.

Unlike other forms of membership-based healthcare, concierge practitioners typically accept healthcare insurance and Medicare in addition to their membership fees. As a result, they are required to bill members’ insurance providers and accept co-pays just like traditional healthcare providers, for all services not covered by their membership fee.32 Further, the acceptance of medical insurance by concierge physicians mandates that they comply with various governmental regulations such as the Medicare Access and CHIP Reauthorization Act of 2015 (MACRA), and other state insurance regulations.33

Direct Primary Care (DPC) Medicine

A similar, albeit different healthcare delivery model from concierge medicine, is direct primary care (DPC). Like concierge medicine practices, DPC practices are available 24/7, 365 days/year, and are sometimes dubbed “blue-collar concierge medicine.”34 While DPCs also charge their members a membership fee (average $65-125/month for adults), with older adults (65+) paying higher rates, the fee is generally less than that of concierge medical practices.35-36 Membership fees are typically billed monthly or annually. In addition, some DPCs may also charge per-visit fees and additional flat rate fees for select treatments or procedures. Note however, that while any additional patient-practitioner per-visit fee may not exceed one’s monthly membership fee, the same does not apply to add-on services (laboratory, radiology, etc.).37 Membership fees typically cover unlimited routine primary care services (sick visits, medication review and follow-ups, annual physical exams including basic laboratory tests, etc.).38 Advanced laboratory tests, radiology and other diagnostics (such as electrocardiograms) may be subject to ancillary fees. Specialist visits, complex urgent care, hospitalization, advanced diagnostic testing (MRI, PET scan, etc.) and prescription drugs are services not commonly covered by a DPC membership fee. Some DPC practices offer tiered membership pricing plans with varying levels of covered benefits, with more advanced minor specialty services offered to those paying more.39

Online organizations such as DPC Nation and DPC Alliance provide an overview of DPC, while highlighting membership benefits.40-41 Because DPC practices do not accept or process services through any insurance provider, including Medicare and Medicaid, they reportedly have lower overhead costs and more time to spend with patients. This includes same day and next day appointments, either in person or via email or a phone call.35 They emphasize the power of group purchasing (wholesale prescription suppliers) and their partnerships with other services providers (laboratory and diagnostic radiology) for their members.42-43

There are some limitations, most notably the need to maintain a traditional healthcare plan to cover the cost of catastrophic injuries or illnesses; i.e., those requiring hospitalization, surgery, and long-term specialized care (cardiac event, stroke, cancer, fractures, etc.). For those with a limited budget, high deductible, catastrophic plans are commonly recommended. In fact, a DPC plan coupled with a high-deductible health plan (HDHP) may be advantageous for those with a limited healthcare budget. For example, when the combined cost of a HDHP (for example $5,000 deductible) plus the monthly fee for a DPC membership is less than the cost of lower, but limited pre-deductible traditional healthcare plan, a DPC membership may be beneficial.44

Another alternative for DPC members is joining a “healthcare cost-sharing community,” such as Sedera Health or MPB Health.38,45-46 Sedera Health and MPB Health members do not pay monthly insurance premiums, rather their members voluntarily contribute a predetermined amount, or “share” each month.46-47 This share contribution is used for medical cost sharing between their members. Expectedly, some healthcare services are not “shareable,” meaning they are ineligible for coverage.46-47 Such health sharing plans may be perceived as viable alternatives for those who are self-employed or are ineligible for a subsidy under the Affordable Care Act. (ACA). Regardless of the reason for consideration, these plans need to be thoroughly researched, with benefits understood prior to joining, as they do not fall under the regulation of the laws governing Affordable Care Act (ACA) compliant plans.44

In contrast to the above-mentioned situations where DPC may prove financially beneficial to consumers, there are several scenarios where DPC may prove less financially sensible, or even more costly. These include consumers who have a low-deductible preferred provider organization (PPO) plan, Medicare/Medicaid, or a health maintenance organization (HMO) plan where referrals are required for all specialist visits.34 The latter would necessitate additional in-network visits to one’s primary care physician in order to attain any needed referrals.

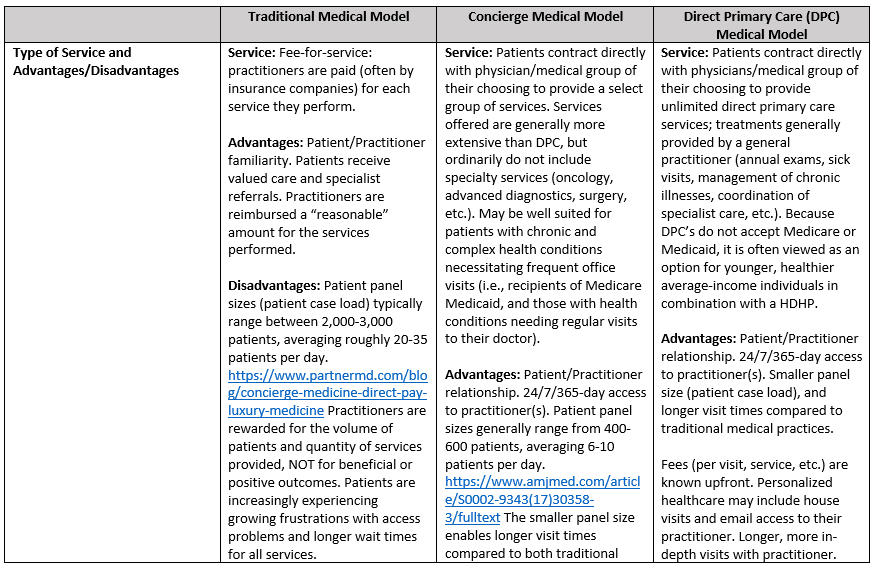

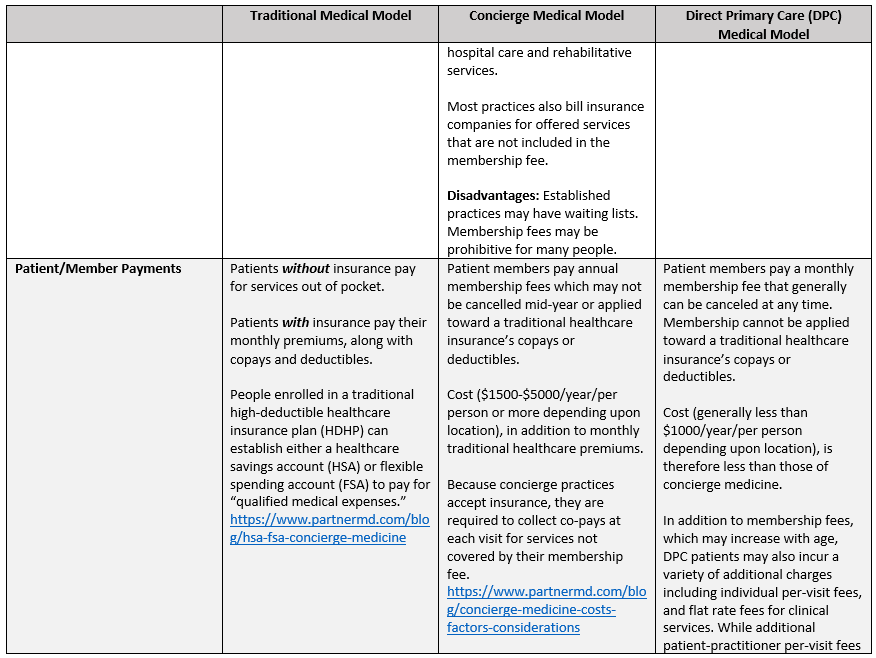

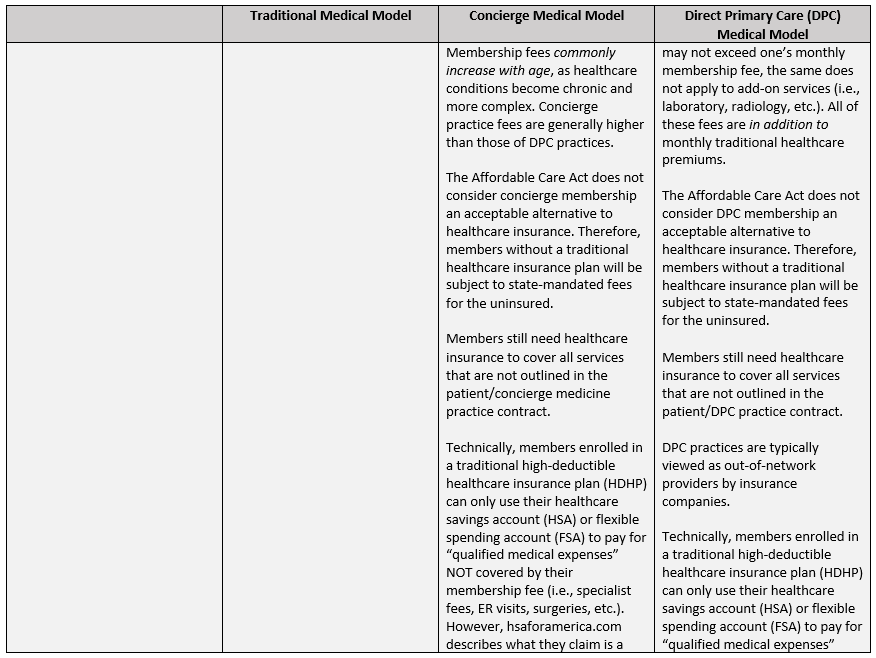

Differences Between Concierge Medicine and Direct Patient Care

While both concierge medicine and direct primary care provide members 24/7, 365-day access to practitioners, there are several fundamental differences between the two. Concierge medical practices tend to provide more comprehensive services, expedited access to specialists, and practitioners who coordinate members’ overall healthcare among all specialists, hospitals and rehabilitative care. Those old enough to remember non-membership-based physician house calls, and visits in the hospital by their primary care practitioner, may really appreciate concierge medical practitioners. Due to the greater number of services and care coordination generally provided by concierge medical practices, their membership fees are typically higher than DPC fees. As a result, the patient population of concierge practices may be less socioeconomically diverse (i.e. generally wealthier) than those found in DPC practices.

Not surprisingly, one very important difference between concierge medicine and DPC is financial in nature. Most concierge medical practices accept private healthcare insurance and/or Medicare, whereas DPC practices do not. This distinction is very important, as healthcare practitioners that accept private or governmental insurance are required to comply with various federal and state mandates. Since DPC providers do not accept insurance, the degree of compliance with various state regulations has garnered increased attention. As of 2020, the vast majority of states “define DPC as a medical service outside of state insurance regulation.”48 As a result, like concierge medicine, DPC needs to be combined with, at minimum, a HDHP in order to avoid incurring a state-mandated fee for opting out of a traditional healthcare plan.35,49

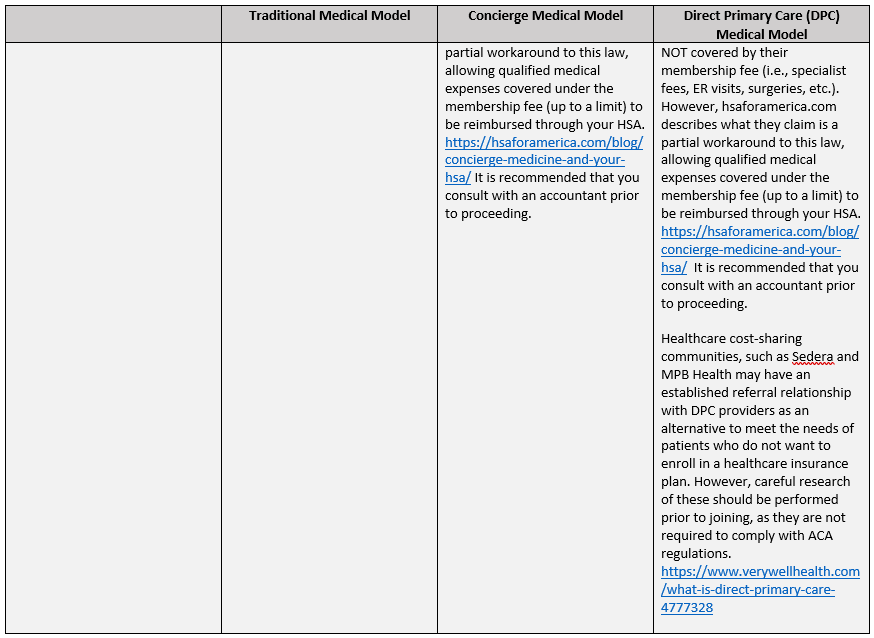

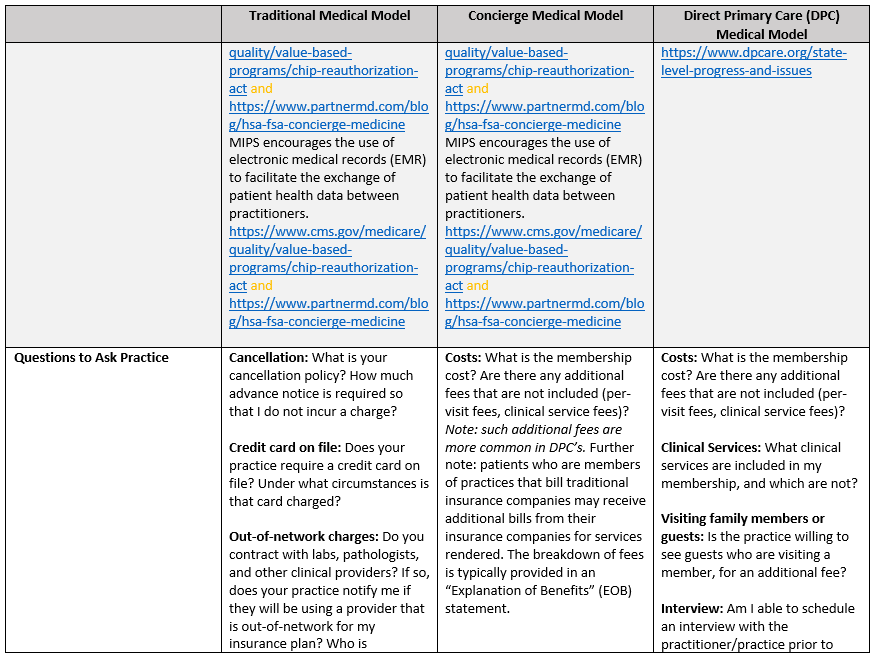

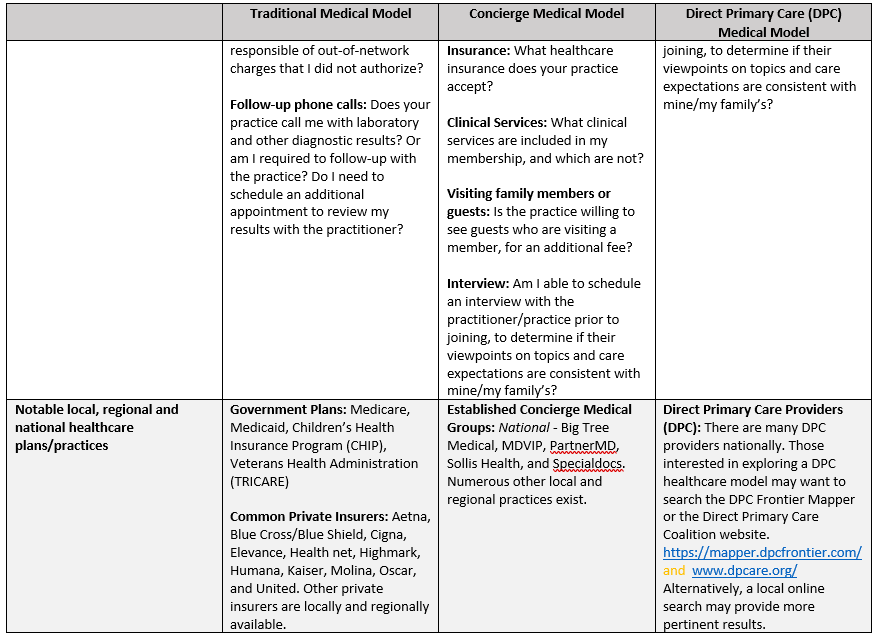

Therefore, it is advised that both concierge and DPC members maintain a traditional healthcare plan to cover essential services not provided by their respective membership plans, such as emergencies (heart attack, stroke, etc.), complex illnesses (cancer, diabetes, degenerative diseases, etc.), and catastrophic injuries (major accidents, etc.), as well as to be in compliance with Affordable Care Act regulations. (See Table 3 in Annex 1, for a more detailed description of the differences between traditional, concierge and DPC healthcare delivery models.)

The Desire for Alternatives to Traditional Patient Healthcare Service

Why do people consider paying hundreds to thousands of dollars per year, in addition to health insurance premiums, just to see a specific practitioner? Is this not yet another example of services catering to the wealthy, that are out of reach for the average American? Didn’t physicians take an oath (Hippocratic) to care for all patients, regardless of their financial status? The answer to the first question is that people of all income levels are tired of waiting weeks to months to see their regular practitioner. They don’t want to have to resort to visits to urgent care or the emergency room, where costs are higher and they have no relationship with the attending practitioner. They want someone who will take the time to listen to what is ailing them, answer their questions, and not leave them with the perception that they were just rushed through an assembly line of care. As to the second question, yes, in all likelihood many wealthier families comprise a large percentage of the clientele at concierge medical practices. After all, it is a fee on top of, not a replacement for, medical insurance. However, there appears to be a growing number of middle-class families that are opting in to either direct patient care (DPC’s) or concierge medicine practices, for the aforementioned reasons. Some may elect to prioritize their ability to see a healthcare practitioner over vacations and other nonessential items. Others, already struggling to pay healthcare premiums, will simply be unable to afford the added service. As for the final question, yes, physicians did take an oath to care for all patients. However, they did not take an oath to be paupers. Many have medical school loans to pay off, families to support, and some even desire a reasonable work-life balance. Additionally, more and more physicians who have been practicing for several decades have grown increasingly dismayed by the changes in the healthcare system. They no longer see the value in the fee-for-service model that encourages patient volume over quality. Nor do all agree with the ubiquitous vertical integration that has slowly become mainstream in healthcare, and the resulting direct and indirect limitations it places on them. Many agree with their patients who feel office visits are rushed. As a result, they desire smaller patient-loads, where they can have more in-depth visits with their patients, all of whom are reportedly discouraged by the traditional fee-for-service healthcare delivery model.

Are Concierge and DPC Healthcare Delivery Models Worth it?

Physicians

Are these alternative healthcare delivery models worth it? According to the American Academy of Family Practitioners, specialty members who migrated their practice to a DPC model reported improved: (a) “overall (personal and professional) satisfaction” (99%), (b) “ability to practice medicine” (99%), (c) “quality of care provided to patients” (98%), and (d) “relationships with patients” (98%).50 Additionally, DPC providers (54%) were more likely than non-DPC practitioners (14%) “to enjoy their work and have no symptoms of burnout.”50

Similarly, in 2023 Specialdocs Consultants, a company that assists physicians in converting to and managing a concierge practice, conducted a poll of its affiliates regarding the “State of the Concierge Physician Medical Practice.”51 No affiliate reported being “overextended or overworked.”49 While 90% of respondents identified “additional time to develop relationships with patients” and 65% reported “a better work-life balance with personal and family time,” as “the two most rewarding aspects of converting to concierge medicine.”51

Patients

For patients, the answer likely depends on a variety of considerations, not the least of which is one’s perception of the accessibility and quality of care generally available in their community. For some, satisfaction with a healthcare provider extends beyond perceived excellence in one’s specialty to include: (1) friendly office staff – online practitioner ratings reinforce that the vast majority of today’s front-office personnel lack cordial communication skills. (2) calm demeanor – the rare, but prized ability to appear calm in even the most trying situations, (3) non-condescending attitude – no one enjoys being the recipient of condescension or patronization when they are seeking assistance for a medical issue and (4) reasonable wait times. Those who have access to a traditional primary care provider who are able to meet these unexceptional needs are fortunate. But for those who don’t, DPC and concierge medicine are worthwhile considerations.

Patient Satisfaction with Concierge or DPC Membership

Concierge medicine and DPC practitioners have a very straightforward way of determining if their patients are satisfied with their services. Patients demonstrate their satisfaction by their willingness to renew their memberships. In other words, they vote with their wallets. What could be simpler than that?

Critics

Critics of concierge and DPC medicine have long purported that the respective healthcare models are not scalable to the general population, and therefore only serve to widen the divide between socioeconomic classes. Further, opponents suggest that there is a risk for healthcare services to be both overutilized and misused by members, thereby negatively impacting those with traditional healthcare insurance.52 Finally, by limiting the number of patients accepted, critics believe concierge and DPC practitioners only exacerbate the current physician shortage.52

U.S. Healthcare Delivery Models Compared to Other Countries

While the aforementioned disparities may be true, where might we look for a superior alternative? No country has a perfect universal health plan. In fact, many countries with universal healthcare also, tellingly, have private healthcare insurance to supplement their countries’ universal healthcare program (Australia, UK, Canada, Germany, Norway).53 Some countries even mandate their citizens to purchase private insurance or face fines (Netherlands and Switzerland), while others provide select plans on a regional or national marketplace (Swiss and Dutch).51 The latter are similar to plans offered on the United States’ ACA exchanges.53

Quality healthcare is measured by many factors, some more objective than others depending upon who is evaluating it. The current U.S. healthcare system has its challenges, just like other countries’ universal health plans. Healthcare systems around the world are plagued by long wait times. The Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) published “Wait Times for Health Services: Next in Line” (2020) using data from “2013 and 2016 Commonwealth Fund International Health Fund Surveys.”54 The 2016 data reveal that while only Canada (33%) surpasses the U.S. (28%) in “the share of people who sometimes, rarely or never get an answer from their regular doctor’s office on the same day,” Canada (61%), Norway (61%), Sweden(52%), New Zealand (48%), the United Kingdom (41%), Australia (39%) and France (36%) all exceed the U.S. (27%) for “the share of people waiting one month or more for a specialist appointment [emphasis added].”54 For a number of countries, wait times have at best remained stagnant, or worse, increased from 2008 to 2018.52 While all countries attempt to deal with long wait times and physician shortages, concierge medicine and DPC, like private insurance in other countries, may provide options for U.S. consumers willing and able to take advantage of their benefits. Health inequality is a worldwide issue, not just a U.S. one. Currently, no one system meets everyone’s needs. Until one does, consumers, providers and corporations will attempt to address perceived gaps.

Summary

Consumers frustrated with access problems, long wait times and lack of continuity of care view membership-based concierge and DPC healthcare models as viable alternatives to the traditional U.S. healthcare model. Members show their satisfaction by their voluntary continuous enrollment. Physicians show their satisfaction by continuing to participate in said business models. Are there trade-offs; i.e., lack of patient diversity, the potential for overutilization of select services, and possible regulatory risks? Certainly. But for those willing to sacrifice to afford an alternative care model, or those fortunate enough to have the resources to afford these models, the option exists.

Membership-based healthcare is expected to surge in the coming decades. Grand View Research estimated the 2023 concierge medicine market size in the United States to be roughly 6.7 billion dollars, with a projected revenue share of 13.3 billion in 2030 – a nearly 100% increase in just seven years.55 Thus, its impact on the U.S. healthcare system, especially the current and projected physician shortage, will depend on how players in the health system respond to its growth. As Bill Gates once said, “Every change forces all the companies in an industry to adapt their strategies to that change.”56 Let’s hope that the positive aspects of membership-based healthcare can break down the vertical integration and monolithic standardization of protocol-driven, non-personalized healthcare that both patients and physicians are dissatisfied with. If so, a truly patient-physician collaborative approach may be available to members of traditional healthcare plans, thereby making U.S. healthcare better, more collaborative, and effectively efficient.

Annex I

Tables

Table 1: Summary of Jain’s Trilliant Health 2023 Trends Shaping the Health Economy 4

| Ten Trends Shaping the Health Economy | |

| Eroding commercial market | A decline in people insured through commercially available plans (employer sponsored, Affordable Care Act Marketplace, and insurance purchased directly from private insurers); plans that account for the largest share of profit revenues (2018-2022). |

| Medicaid disenrollment resulting from the yearly recertification process | |

| The “silver tsunami” – an aging baby boomer population that is not offset by births (2017-2022). | |

| Migration of Americans, including those aged 20-39 (2022), from expensive coastal areas in the Northeast and Western states to the Sunbelt (especially TX and FL). Many being commercially insured patients. These trends are expected to alter the current healthcare demand and supply in each market. | |

| Increasing state expenditures allocated to Medicaid. | |

| A decline in payer mix, the percentage of patients covered by the various forms of health insurance (commercial insurance, direct pay insurance, Medicare/Medicaid) (2016-2022, with the most significant occurring between 2021-2022). | |

| Unraveling of health of American consumers | A dramatic increase in mortality rates for those under 40 years of age (2018-2022), largely attributed to overdose deaths in 42 states. States leading this dismal statistic: California (117.1% increase), Washington (112.9% increase) and Tennessee (102.9% increase). |

| Increasing delays in seeking healthcare for all types of care with the exception of mental health (2021-2022). Reasons cited for the delay included lack of healthcare insurance, the high cost of healthcare insurance and the overall high cost of living. These delays contributed to a reduction in primary care services and preventive care measures, and a greater increase in morbidity and mortality, and early-onset cancer. Unfortunately, cancer mortality has been increasing for Americans ages 35-44, while decreasing for those 45-64 (2018-2022). Myocarditis has also seen a significant jump in young adults aged 18-44, while remaining fairly stable in the 45-64 and 65+ age groups (2018-2022). | |

| Rising prescription drug prices resulted in a growing number of Americans (Especially low-income Americans) not adhering to a prescription regimen prescribed by the healthcare provider (2021). | |

| Investments in prescription drugs and diagnostics | Pharmaceutical companies are allocating many billions of dollars to the development of immunological, cancer and rare disease treatments. “High costs, supply shortages, administration challenges and a very involved patient journey” impact the patient’s ability to receive these new therapies. |

| A non-enthusiastic demand for healthcare services | Inpatient admissions and surgeries, and primary care preventive services have decreased from 2017-2022. A direct correlation between Americans with chronic diseases and comorbidities and inpatient hospital admissions does not appear to exist. Furthermore, the demand for select healthcare services does not appear to be a function of geographical size, but rather “disease burden” in any given area. |

| The projected demand for various surgical specialties from 2023-2027 is mixed. Heart/Vascular inpatient procedures are projected to be greater than outpatient procedures. In contrast, OB/GYN, Spine/Neuro, Orthopedic, and Digestive outpatient procedures are projected to outperform inpatient procedures. | |

| Newer less invasive procedures tend to result in revenue losses for providers. | |

| Consumer behaviors revealing patient decision making practices | A growing dissatisfaction with American healthcare, and the quality of care received (2010-2022). Wide ranging share-of-care, or patient loyalty, measurements. For example, New York has the widest share-of-care measurements range from 25.1% – 81.6%, while North Dakota has the thinnest, 68.8% – 75.9%. |

| More eligible Medicare Americans are switching from traditional Medicare plans to Medicare Advantage plans (2006-2022). Although this may have been the case at the time of Jain’s analysis, a growing number of healthcare reports challenge this projection. Thanks to increasing prior authorization denials, slow payments, and fraud allegations, both healthcare providers and plan members are rethinking Medicare Advantage plans.57-58 | |

| Approximately 40% of Americans prefer to self-diagnose using online search results, rather than seeing a primary care physician (2023) | |

| There is an inverse relationship between patient age and those who would prefer to receive non-urgent care from a pharmacy rather than a traditional physician office (2022); Gen Z = 56%, Millennials = 54%, Gen X = 40% and Baby Boomers = 35%. CVS’s decision to open and then shutter many of their MinuteClinics will undoubtedly influence local care services.59 | |

| Post-COVID telehealth use is waning (2022). Females disproportionately use telehealth services more than males. Behavioral health is the primary service obtained from telehealth providers. | |

| Elimination of traditional healthcare intermediaries | A growing number of newer players (Walmart, CVS Health and Minute Clinics, Amazon One Medical, etc.) are delivering non-urgent (primary) care, with pharmacy-associated new entrants being able to fill prescriptions on premises. Whether the intention is to replace primary care providers or not, the result is the same: It has the potential to delay care for high-acuity conditions. |

| Increasing number of surgeries being performed at ambulatory surgical centers (ASCs) (22.2% in 2022, up from 21.8% in 2021). | |

| Aside from increasing retail-based care providers (noted above), the number of home-based providers has also shown a gradual increase, which is not surprising given the growth of ASCs. | |

| Constrained supply of providers | Year-over-year, the supply of all physicians (MD and DO) has declined. From 2018-2022 there has been a net change of -2.3%. United Health Group (United Healthcare and Optum) and Kaiser Permanente employ nearly 10% of all active Physicians in the US. |

| New healthcare market service providers are competing with traditional health services providers from a smaller pool of physicians. Thirteen-year projections (2022 – 2035) indicate that pulmonologists will be least impacted, while nephrologists will see the greatest impact. Similarly, within the mental health sphere, psychiatric nurse practitioners are projected to see the greatest impact, and adult psychiatry the least. In fact, nurse practitioners as a whole are projected to see the greatest impact of all allied health professionals. | |

| The continued growth of new entrants (cosmetic companies, consulting firms, insurers, etc.) into the healthcare services marketplace who are competing for all healthcare providers is having an impact on the number of primary care providers sufficient to service the needs of Americans. | |

| Overstated monopolistic effects | Hospitals continue to report financial losses, while newer players, like Optum, are reporting billions in increased revenues after signing deals with hospitals. The Federal Trade Commission (FTC) is understandably looking into these deals for their anti-competitive impacts (2023). |

| Markets viewed as monopolistic for select services do not necessarily have the highest rates for that service. Based upon the Herfindahl-Hirschman Index (HHI), a metric used to determine market competitiveness, the disparity between payer (insurance companies) – provider (healthcare facilities and providers) concentration in geographical areas typically influence which side has the negotiating power in dictating reimbursement rates. | |

| Monopolistic healthcare providers (often resulting from hospital and physician consolidation) are not associated with greater quality of healthcare, or higher service prices. Rather, geographical location appears to correlate more closely with price (higher prices in Northeast and West coasts, and lower in the Southeast). | |

| Employers paying more for less healthcare services | Healthcare costs have outpaced overall consumer costs from 2000-2023 (114.3% to 80.8%). Both employer and employee high-deductible healthcare plan contributions have risen since 2010. Not surprisingly, more and more employers are turning to self-insured coverage (65%), whereby the employer, and not an insurance company, is ultimately responsible for covering employee healthcare claims (2023) |

| Commercial insurers reimburse hospitals and physicians nearly twice what Medicare does (2013-2018) | |

| Insurers (Anthem BCBS, United Healthcare, etc.) typically pay different providers in the same city (various hospitals and ACSs) vastly different prices for identical services. The same applies for both inpatient and outpatient services. Sadly, negotiated rates are not correlated with higher quality care in competitive markets, such as New York City or Los Angeles (2023). | |

| As a result of the above, insurers and employers are working together to force hospitals to comply with Federal price transparency laws, assess hospital billing practices and promote competition among hospitals by establishing relationships with providers who have lower healthcare costs for the same or higher quality services. | |

| Lower than expected market rate returns | Hospital expenses continue to rise despite declining hospital admissions (1980-2021), especially services provided at teaching hospitals (2023). The same applies for outpatient preventative services, such as colonoscopies, that had a negotiated median price range of $368 – $836 nationally. |

| The Congressional Budget Office (2022) has shown a willingness to work with commercial insurers to “cap” rates paid to hospitals and physicians, similar to that for Medicare/Medicaid. This concept has been gaining consideration among several state legislatures, which if enacted has the potential to negatively impact hospitals by millions of dollars/year. | |

| The Medicare Advisory Commission (2023) has recommended establishing “site-neutral” payments for all procedures performed in an ambulatory outpatient setting; i.e., ambulatory care centers, hospital outpatient procedures, physician offices. | |

| The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services Drug Price Negotiation Program have begun negotiating with pharmaceutical companies to reduce the market rate for common exceptionally expensive drugs (2023-2026). Whether the negotiated prices will transfer to the commercial insurer market is questionable given the substantial lobbying efforts undertaken each year by pharmaceutical and life science companies. | |

Table 3: Succinct Overview of the Similarities and Differences Between Traditional, Concierge and Direct Primary Care Healthcare Delivery Models.69

Works Cited

Works Cited

1. Kiang, Mathew V., et al. “Excess Mortality among US Physicians during the COVID-19 Pandemic.” JAMA Internal Medicine, JAMA Network, 1 Apr. 2023, jamanetwork.com/journals/jamainternalmedicine/fullarticle/2800889.

2. “Why We Counted Every US Healthcare Worker Who Died from Coronavirus for a Year.” The Guardian, Guardian News and Media, 8 Apr. 2021, www.theguardian.com/us-news/ng-interactive/2020/dec/22/why-were-counting-every-us-healthcare-worker-who-dies-from-coronavirus.

3. IHS Markit Ltd. “The Complexities of Physician Supply and Demand: Projections from 2019 to 2034.” Association of American Medical Colleges, Association of American Medical Colleges, 2021, http://www.aamc.org/media/54681/download.

4. Jain, Sanjula. “2023 Trends Shaping the Health Economy.” Trilliant Health, Trilliant Health, 25 Oct. 2023, http://www.trillianthealth.com/hubfs/TH_Annual%20Report_2023.10.25%20(2).pdf?hsCtaTracking=e0a5d398-f873-4e1f-b574-54c459b40597%7C64ca9886-cf47-4a6f-9a43-814418eb9864.

5. “2022 Survey of Physician Appointment Wait Times and Medicare and Medicaid Acceptance Rates.” Washington State Hospital Association, AMN/Merritt Hawkins, 5 Jan. 2023, http://www.wsha.org/articles/new-survey-physician-appointment-wait-times-getting-longer/.

6. “2017 Survey of Physician Appointment Wait Times and Medicare and Medicaid Acceptance Rates.” AristaMD, AMN/Merritt Hawkins, Nov. 2018, http://www.aristamd.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/11/mha2017waittimesurveyPDF-1.pdf.

7. Mejia, Brittny, and Jack Dolan. “How We Reported the Story: Deadly Delays in L.A. County’s Public Hospital System.” Los Angeles Times, Los Angeles Times, 2 Oct. 2020, http://www.latimes.com/california/story/2020-09-30/delays-los-angeles-hospitals-behind-the-story.

8. “Study: Nearly 3 in 4 Americans Say It’s Easier to Go to the ER Than to Get a Doctor’s Appointment.” Zocdoc, Zocdoc, 19 May 2022, http://www.zocdoc.com/about/news/2019-er-report/.

9. “Estimates of Emergency Department Visits in the United States, 2016-2021.” Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 6 July 2023, http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/dhcs/ed-visits/index.htm.

10. “Compare E.R. Wait Times of All U.S. Hospitals.” Hospital Stats, Hospital Stats, http://www.hospitalstats.org/ER-Wait-Time/. Accessed 19 Feb. 2024.

11. Sullivan, DJ, and Travis Ansel. “Patient Share of Care: Share of Wallet for Healthcare.” HSG Advisors, HSG Advisors, 2021, hsgadvisors.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/09/HSG_SHSMD-PNIA-White-Paper-DIGITAL-final.pdf.

12. Assistant Secretary for Public Affairs (ASPA). “About the ACA.” HHS.Gov, US. Department of Health and Human Services, 15 Mar. 2022, http://www.hhs.gov/healthcare/about-the-aca/index.html.

13. Nguyen, Tran. “California Is Expanding Health Care Coverage for Low-Income Immigrants in the New Year.” AP News, AP News, 30 Dec. 2023, apnews.com/article/california-medicaid-expansion-undocumented-immigrants-34d8deb2186e9195b253f499e81a3d77.

14. “Older Adult Expansion.” Dhcs.ca.Gov, California Department of Health Care Services, http://www.dhcs.ca.gov/services/medi-cal/eligibility/Pages/OlderAdultExpansion.aspx. Accessed 21 Feb. 2024.

15. “Young Adult Expansion.” Dhcs.ca.Gov, California Department of Health Care Services, http://www.dhcs.ca.gov/services/medi-cal/eligibility/Pages/youngadultexp.aspx. Accessed 21 Feb. 2024.

16. Paluch, Jennifer, and Joseph Herrera. “Homeless Populations Are Rising Around California.” Public Policy Institute of California, Public Policy Institute of California, 14 Apr. 2023, http://www.ppic.org/blog/homeless-populations-are-rising-around-california/#:~:text=As%20of%202022%2C%2030%25%20of,of%20the%20nation’s%20homeless%20population.

17. Hwang, Kristen. “More Street Medicine Teams Tackle the Homeless Health Care Crisis.” CalMatters, CalMatters, 8 Dec. 2022, calmatters.org/health/2022/12/homeless-health-care/.

18. Ibarra, Ana B. “Year in Review: California Tackles Mental Health, Fentanyl.” CalMatters, CalMatters, 19 Dec. 2023, calmatters.org/health/2023/12/california-mental-health-fentanyl-crisis/.

19. Karlamangla, Soumya. “Millions of Californians Are Expected to Lose Medi-Cal Coverage.” The New York Times, The New York Times, 17 July 2023, http://www.nytimes.com/2023/07/17/us/california-medi-cal-coverage.html#:~:text=More%20than%2015%20million%20Californians,coverage%20to%20low%2Dincome%20residents.

20. Schrupp, Kenneth. “California’s Free Medi-Cal to Cover Illegal Immigrants Amid Healthcare Shortage .” The Foreign Desk | by Lisa Daftari , The Foreign Desk/ The Center Square, 28 Dec. 2023, foreigndesknews.com/us/californias-free-medi-cal-to-cover-illegal-immigrants-amid-healthcare-shortage/.

21. Pipes, Sally. “No ‘California Dreamin’ for Single Payer Healthcare.” Newsmax, Newsmax Media, Inc., 4 Apr. 2023, http://www.newsmax.com/sallypipes/california-single-payer-healthcare/2023/04/04/id/1114956/.

22. “4 Things You Didn’t Know About Concierge Medicine History.” Dedication Health | Innovative Concierge Medicine, Dedication Health, 5 Aug. 2018, http://www.dedication-health.com/concierge-medicine-history/#:~:text=The%20first%20concierge%20medical%20practice,%2413%2C200%20to%20%2420%2C000%20per%20family.

23. Ashford, Kate. “What Is Concierge Medicine? (And Should You Consider It?).” Edited by Tina Orem, NerdWallet, 19 May 2023, http://www.nerdwallet.com/article/health/medical-costs/consider-concierge-medicine.

24. Beverly Hills Concierge Doctor, Beverly Hills Concierge Doctor, beverlyhillsconciergedoctor.com/. Accessed 21 Feb. 2024.

25. “Exploring the Nuances: 15 Key Differences Between Concierge Care vs Direct Primary Care.” Health Compiler, Health Compiler, 1 Feb. 2024, http://www.healthcompiler.com/key-differences-between-concierge-care-and-direct-primary-care.

26. Ito, Robert. “L.A.’s Concierge Medical Services Woos VIPS with Plush Amenities — but Not Everyone Thinks That’s Healthy.” Los Angeles Magazine, Los Angeles Magazine, 1 Apr. 2021, lamag.com/featured/concierge-medicine-los-angeles.

27. Dalen, James E., and Joseph S. Alpert. “Concierge Medicine is Here and Growing!!” The American Journal of Medicine, vol. 130, no. 8, Aug. 2017, pp. 880–881, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjmed.2017.03.031.

28. “Concierge Medicine Today’s Industry Insights, 2024 Annual Report.” Concierge Medicine Today, Concierge Medicine Today, 2024, http://www.conciergemedicinetoday.net/insights.

29. “Penn Personalized Care.” Pennmedicine.Org, Penn Medicine, http://www.pennmedicine.org/for-patients-and-visitors/find-a-program-or-service/primary-care/penn-personalized-care. Accessed 21 Feb. 2024.

30. “Premier Concierge Medicine and Executive Physicals: Where Health and Hospitality Meet.” University of Miami Health System, University of Miami Health System, umiamihealth.org/treatments-and-services/uhealth-premier/concierge-medicine. Accessed 21 Feb. 2024.

31. “Duke Signature Care.” Duke Health, Duke Health, 11 Mar. 2021, http://www.dukehealth.org/treatments/duke-signature-care.

32. Smith, Zack. “Concierge Medicine: Costs, Factors, and Considerations.” PartnerMD, PartnerMD, 27 Apr. 2023, http://www.partnermd.com/blog/concierge-medicine-costs-factors-considerations.

33. Eramo, Lisa. “5 Legal Considerations with Concierge Medicine.” The Intake, The Intake, 27 Oct. 2023, http://www.tebra.com/theintake/patient-experience/legal-and-compliance/5-legal-considerations-with-concierge-medicine.

34. “Frequently Asked Questions.” Ciampi Family Practice, Ciampi Family Practice, http://www.ciampifamilypractice.com/frequently-asked-questions. Accessed 20 Feb. 2024.

35. “Direct Primary Care: Evaluating a New Model of Delivery and Financing.” Society of Actuaries, Society of Actuaries, May 2020, http://www.soa.org/globalassets/assets/files/resources/research-report/2020/direct-primary-care-eval-model.pdf.

36. Rosenberg, Alex. “What Is Direct Primary Care, and How Much Does It Cost?” MarketWatch, MarketWatch, 27 Apr. 2023, http://www.marketwatch.com/story/what-is-direct-primary-care-and-how-much-does-it-cost-125df60.

37. “Defining Direct Primary Care.” Direct Primary Care Frontier, Direct Primary Care Frontier, http://www.dpcfrontier.com/defined. Accessed 20 Feb. 2024.

38. “Frequently Asked Questions.” DPC Nation, DPC Nation, dpcnation.org/faq/. Accessed 19 Feb. 2024.

39. “DPC Health – Individual Plans.” DPC HealthTM, DPC HealthTM, 25 July 2023, dpchealth.com/membership-plans/.

40. “What Is Direct Primary Care?” DPC Nation, DPC Nation, dpcnation.org/. Accessed 20 Feb. 2024.

41. “DPC Doctors Helping DPC Doctors.” DPC Alliance, DPC Alliance, 5 Oct. 2023, dpcalliance.org/.

42. “Member Benefits.” DPC Alliance, DPC Alliance, 5 Oct. 2023, dpcalliance.org/member-benefits/.

43. “What Is Direct Primary Care (DPC)?” DPC Alliance, DPC Alliance, 5 Oct. 2023, dpcalliance.org/about/what-is-direct-primary-care-dpc/.

44. Norris, Louise. “How Does Direct Primary Care Work?” Verywell Health, Verywell Health, 1 Sept. 2023, http://www.verywellhealth.com/what-is-direct-primary-care-4777328.

45. “Direct Primary Care + Sedera = Total Healthcare Solution.” Sedera Medical Cost Sharing, Sedera Medical Cost Sharing, assets.ctfassets.net/01zqqfy0bb2m/6Wf8PGxytH5aDYecniTzBh/053c529f4836e991ef936bcddf678656/DPC_CoBranded_Generic.pdf. Accessed 19 Feb. 2024.

46. “Frustrated With Your Healthcare Plan?” MPB Health, MPB Health, mpb.health/. Accessed 19 Feb. 2024.

47. “An Affordable Way for Managing Healthcare Costs.” Sedera, Sedera, sedera.com/. Accessed 19 Feb. 2024.

48. “State Policy.” Direct Primary Care Coalition, Direct Primary Care Coalition, http://www.dpcare.org/state-level-progress-and-issues. Accessed 22 Feb. 2024.

49. Kona, Maanasa, et al. “Direct Primary Care Arrangements Raise Questions for State Insurance Regulators.” The Commonwealth Fund, The Commonwealth Fund, 22 Oct. 2018, http://www.commonwealthfund.org/blog/2018/direct-primary-care-arrangements-state-insurance.

50. “2022 Direct Primary Care.” American Academy of Family Physicians, American Academy of Family Physicians, http://www.aafp.org/dam/AAFP/documents/practice_management/direct-primary-care-2022-data-brief.pdf. Accessed 19 Feb. 2024.

51. Bauer, Terry. “Thankful for Change: Concierge Physicians Grateful to Practice Medicine Their Way, According to New Survey from Specialdocs.” Yahoo! Finance, Yahoo! Finance, 27 Nov. 2023, finance.yahoo.com/news/thankful-change-concierge-physicians-grateful-191500896.html.

52. Marquez, Denisse Rojas, and Hazel Lever. “Why VIP Services Are Ethically Indefensible in Health Care.” American Medical Association Journal of Ethics®, American Medical Association, 2023, journalofethics.ama-assn.org/article/why-vip-services-are-ethically-indefensible-health-care/2023-01.

53. Tikkanen, Roosa. “Variations on a Theme: A Look at Universal Health Coverage in Eight Countries.” The Commonwealth Fund, The Commonwealth Fund, 22 Mar. 2019, http://www.commonwealthfund.org/blog/2019/universal-health-coverage-eight-countries#:~:text=One%20way%20to%20achieve%20universal%20coverage%20is%20through,marketplace%2C%20while%20the%20Swiss%20shop%20on%20regional%20marketplaces.

54. “How Long Are Waiting Times Across Countries?” Waiting Times for Health Services: Next in Line, OECD Publishing, 2020, https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/sites/242e3c8c-en/1/3/2/index.html?itemId=/content/publication/242e3c8c-en&_csp_=e90031be7ce6b03025f09a0c506286b0&itemIGO=oecd&itemContentType=book. Accessed 20 Feb. 2024.

55. Grandview Research, 2023, U.S. Concierge Medicine Market Size, Share & Trends Analysis Report by Specialty, by Ownership, and Segment Forecasts, 2024-2030, https://www.grandviewresearch.com/industry-analysis/us-concierge-medicine-market-report. Accessed 22 Feb. 2024.

56. Indeed Editorial Team. “40 Change Management Quotes to Inspire the Entire Team.” Indeed, Indeed, 2022, ca.indeed.com/career-advice/career-development/change-management-quotes.

57. Emerson, Jakob. “Hospitals Are Dropping Medicare Advantage Plans Left and Right.” Becker’s Hospital Review, Becker’s Hospital Review, 2023, http://www.beckershospitalreview.com/finance/hospitals-are-dropping-medicare-advantage-left-and-right.html#:~:text=Among%20the%20most%20commonly%20cited,and%20slow%20payments%20from%20insurers.

58. King, Robert. “‘It Was Stunning’: Bipartisan Anger Aimed at Medicare Advantage Care Denials.” POLITICO, POLITICO, 24 Nov. 2023, http://www.politico.com/news/2023/11/24/medicare-advantage-plans-congress-00128353#:~:text=HHS’%20Office%20of%20the%20Inspector,that%20should%20have%20been%20approved.

59. Girardin, Shavla. “CVS to Close 25 Minuteclinic Locations in Los Angeles Area by Late February.” ABC7 Los Angeles, ABC7 Los Angeles, 31 Jan. 2024, abc7.com/cvs-minute-clinic-pharmacy-closing/14373029/.

60. Gifford, Melissa. “Concierge Medicine vs. Direct Pay Primary Care vs. VIP Medicine.” partnerMD, partnerMD, 20 June 2023, http://www.partnermd.com/blog/concierge-medicine-direct-pay-luxury-medicine .

61. Lasher, Joe. “How to Use Your HSA or FSA for Concierge Medicine.” PartnerMD, PartnerMD, 17 Apr. 2023, http://www.partnermd.com/blog/hsa-fsa-concierge-medicine.

62. “MACRA: MIPS & APMs.” CMS.Gov, U.S. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, http://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Quality-Initiatives-Patient-Assessment-Instruments/Value-Based-Programs/MACRA-MIPS-and-APMs/MACRA-MIPS-and-APMs. Accessed 27 Feb. 2024.

63. Freedman, Max. “What Are MACRA and MIPS?” Business News Daily, Business News Daily, 23 Oct. 2023, http://www.businessnewsdaily.com/16581-macra-mips.html.

64. Long, Wiley. “Concierge Medicine and Your HSA.” HSA for America, HSA for America, 21 July 2020, hsaforamerica.com/blog/concierge-medicine-and-your-hsa/.

65. Eskew, Phil. “DPC Frontier Mapper.” DPC Frontier, DPC Frontier, mapper.dpcfrontier.com/. Accessed 20 Feb. 2024.

66. “What Is Direct Primary Care?” Direct Primary Care Coalition, Direct Primary Care Coalition, http://www.dpcare.org/. Accessed 22 Feb. 2024.

67. “Rev. Proc. 2023-23.” IRS.Gov, IRS.gov, http://www.irs.gov/pub/irs-drop/rp-23-23.pdf. Accessed 28 Feb. 2024.

68. Rae, David. “The New 2024 Health Savings Accounts (HSA) Limits Explained.” Forbes, Forbes Magazine, 7 Dec. 2023, http://www.forbes.com/sites/davidrae/2023/12/07/what-are-the-new-2024-health-savings-accounts-hsa-limits/.

69. B., Gerry. “The Search for a Quality Physician: The Rise of Alternative Healthcare Delivery Models.” Inside Out Odyssey, Inside Out Odyssey, 5 Mar. 2024, insideoutodyssey.com/2024/03/05/the-search-for-a-quality-physician-the-rise-of-alternative-healthcare-delivery-models/.